Ghazali, the renowned Muslim scholar, was originally from Tus, a town near Mashhad. In those days, around the fifth century after Hijrah, Nishabur was the center and capital of that district and was considered an academic center of learning. Students wishing to acquire knowledge in that district travelled to Nishabur. Ghazali also travelled to Nishabur and Gurgan.

He pursued his studies enthusiastically there and acquired knowledge from his professors and scholars for many years. In order not to forget any points of erudition, or to lose the fruits picked by his own hands, he always took notes of the lectures and made them into pamphlets. He treasured these notes, which were the results of his hard work over many years, as dearly as he treasured his own life.

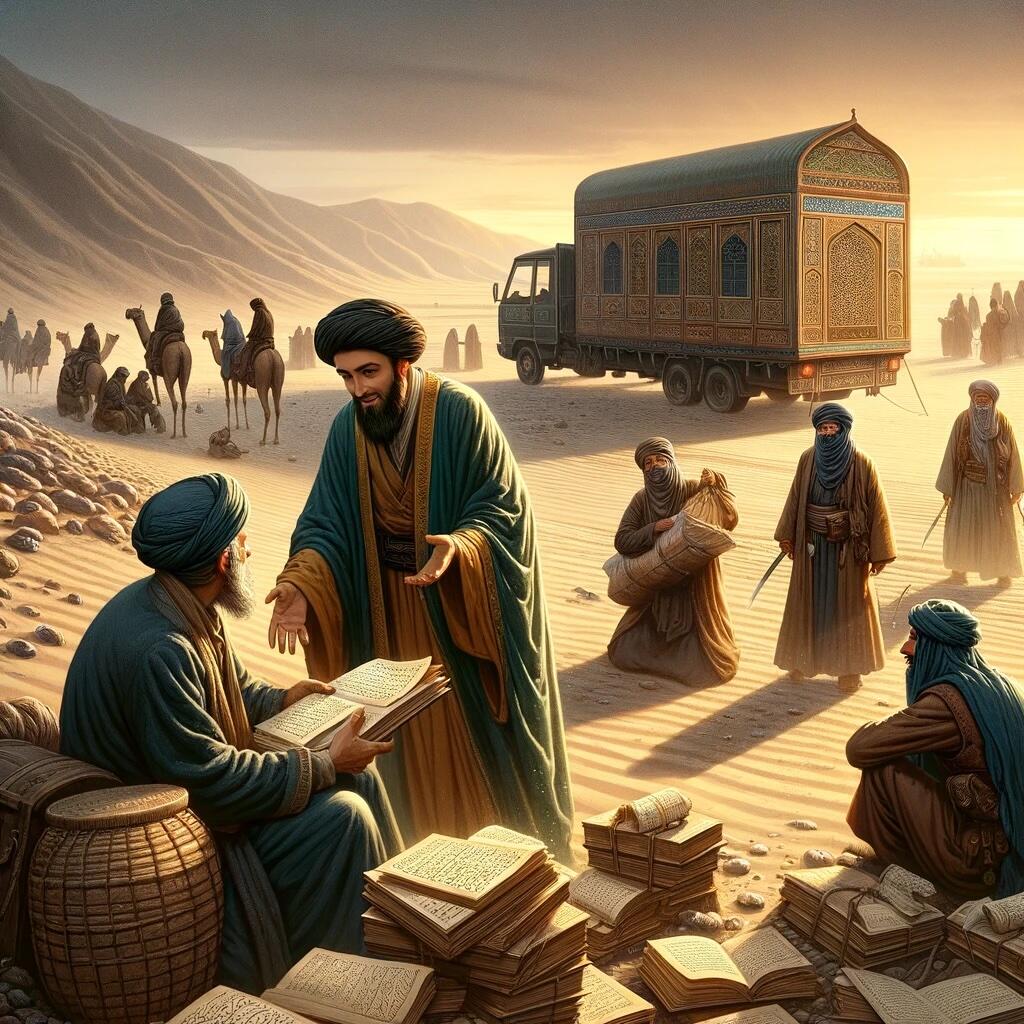

Years later, after completing his studies, he decided to return to his native land. He packed up all his notes, tied them into a bundle and set forth in the company of a caravan towards his home. Suddenly, the caravan came up against a band of thieves. They held up the caravan and robbed whatever property they could find. Eventually it was Ghazali's turn for his property.

As they laid their hands on his bundle of notes, Ghazali began lamenting and pleading and said, “Take whatever I have, but please leave this bundle for me!”

The thieves thought certainly there must be something very precious inside the bundle. They untied it and found nothing but a handful of written papers. They asked, “What are these and of what use are they?”

Ghazali said, “Whatever they may be, they would be of no use to you, but they are of great use to me.”

The thieves said, “But of what use are they to you?”

Ghazali said, “These are the fruits of my hard labour over many years of study. If you take them away from me, my knowledge will perish and all the years of my struggles in the way of knowledge will have been in vain.”

The thieves said, “Well then your knowledge lies amongst these papers, doesn’t it?”

Ghazali said, “Yes.”

The thieves said, “Knowledge which is in a bundle and vulnerable to theft is no knowledge at all. You should re-evaluate your life.”

This simple remark shook Ghazali to the depths of his vigilant soul. He realised that, until that day, he was no better than a parrot, jotting down on paper all that he had heard from his professors. After that day, he thought of doing his utmost to train his mind through reflection, to contemplate more, to research and enjoin useful subjects in his mind.

Ghazali said, “The best advice I have ever received, which became the model for my intellectual life, came from a highway thief.”1